In Texas, as the early 1960s Space Age was just starting to lift off, the venerable Bell Helicopter company began experimenting with a pilot-controlled night vision system. It was a remote viewing device that employed a headset displaying an augmented view of the ground for the pilot via an infrared camera that was mounted under the helicopter. Inventor Ivan Sutherland told Forbes, “My little contribution to virtual reality [VR] was to realize we didn’t need a camera—we could substitute a computer. However, in those days no computer was powerful enough to do the job, so we had to build special equipment.”

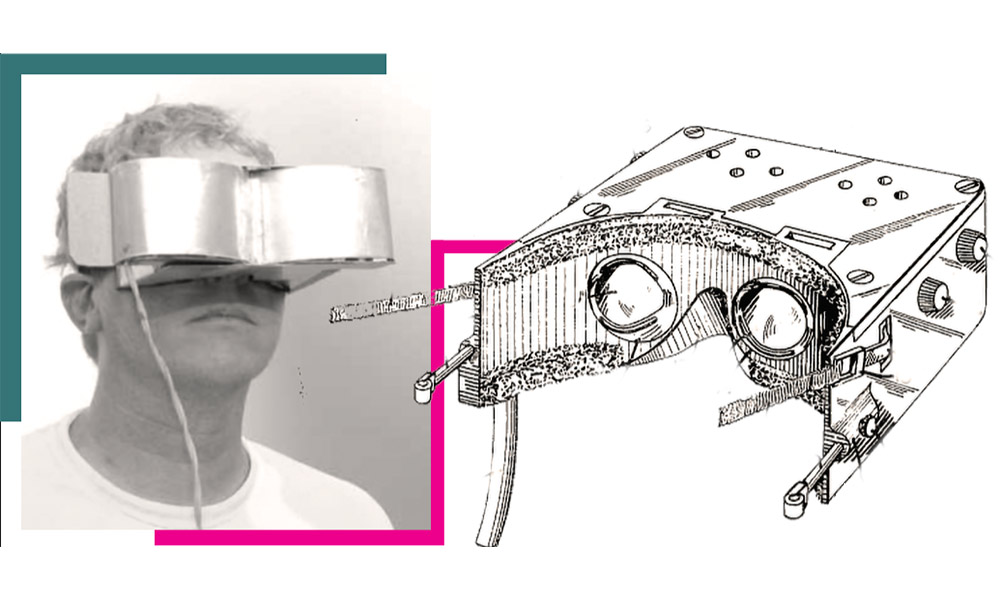

Though it never really got off the ground, Sutherland’s device to assist pilots is considered one of the first head-mounted display (HMD) devices, a category that includes today’s smart glasses. He would go on to invent another headset with the nickname “The Sword of Damocles,” a joke based on the cross shape of the overhead support system. Any ’60s Bond villain would have loved having in their lair such a fearsome-looking contraption.

Still other HMD devices in the ’60s included Morton L. Heilig’s patented “Stereoscopic Television Apparatus for Individual Use”—aka the Telesphere Mask, a whopping two-pound headset that provided 3D television and stereoscopic sound, plus environmental effects like wind. Heilig’s US patent describes “a pair of optical units, a pair of television tube units, a pair of earphones, and a pair of air discharge nozzles, all co-acting to cause the user to comfortably see the images, hear the sound effects, and to be sensitive to the air discharge of said nozzles.”

Heilig’s HMD was designed so that “the apparatus does not sag, and so that its weight is evenly distributed over the bone structure of the front and back of the head, without the necessity of holding the apparatus up by the hand.” He was also inventor of the Sensorama, an immersive artificial reality experience that included pelting users with “rain” or subjecting them to smells redolent of whatever scene—a cityscape perhaps—would be unfolding in Heilig’s cozy simulator booth.

While neither Sutherland’s, nor Heilig’s, nor many other similar devices ever really captured or developed a sustainable market, optics and photonics pioneers have never abandoned the idea of useful AR/VR/MR (augmented, virtual, and mixed reality) headsets and displays. And as the Space Age gave way to the Information Age, their quest has continued with some of the biggest names in Silicon Valley—Google, Meta, Apple, Microsoft, and many more—in hot pursuit of very real AR/VR/MR gold, especially smart glasses.

Smart glasses are not a new idea. Google Glass was released in 2013 but flopped shortly after because they were expensive, had limited functionality, and, frankly, they were ugly. But the electronics industry is not ready to give up on smart glasses. In fact, big-name players in the industry are leaning in, and Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg has gone so far as to forecast that smart glasses will overtake smart phones as primary devices by the 2030s.

Ivan Sutherland’s head-mounted display dubbed “The Sword of Damocles”. Photo credit: DOI:10.13140/RG.2.1.1874.7929

Companies like Meta, Apple, and many others, are teaming up with iconic eyewear brands, for example, Ray-Ban and its parent company Luxottica, to provide customers with what Google’s Bernard Kress calls “an AI assistant for your face. It’s an assistant that is with you, that sees what you see, hears what you hear—but also hears what you see and sees what you hear.” This new assistant is there to make your life—personal and professional—easier.

The marketplace is alive, too, with less well-known products like TranscribeGlass—created by students Madhav Lavakare from Yale University and Tom Pritsky from Stanford University—that displays real-time captions for the deaf and hard of hearing. Their technology incorporates translation features that could also help bridge language barriers.

A similar product with a slightly different market, Xander Captioning Glasses are built to assist people who have hearing challenges, enabling them to understand speech and participate in conversations in a natural way. XanderGlasses, the company says, “translate speech to text in real-time and project accurate captions of conversations that are visible to the wearer only.”

Elbit Systems makes SmartEye, smart ballistic glasses for see-through situational awareness for the military. The head-mounted eyewear can display augmented reality symbology and imagery, while also providing instant identification and registration of images to a 3D imagery database. According to the manufacturer, the glasses can interface with multiple video sources, including weapon sights, unmanned aerial systems, and reconnaissance unit inputs, and they can be integrated with a helmet-mounted night sensor for enhanced operation during night missions.

The widespread adoption of AR/VR/MR, including smart glasses, hinges on two key technologies: waveguides and display engines. Waveguides are micron-thin wafers of glass that manage the flow of light using tiny grating structures etched on their surface. A display engine is a high-intensity beam of light that gets projected into the waveguide to produce an image before the wearer’s eye. The holy grail for optics manufacturers like Vuzix, who provides the waveguide technology for XanderGlasses, is to continue shrinking the waveguides and improving the light engines to deliver a comfortable and enjoyable viewing experience that augments people’s daily lives.

Dozens of other waveguide manufacturers are supplying the AR/VR/MR market with a variety of technology innovations. They design and sell components like waveguide combiners, projection modules, and fully integrated optical engines. One goal is to achieve competitive consumer market pricing for the technology.

The industry movement today is “pro-sumer,” or pro-consumer, Kress says. “That’s the thing we didn’t understand over the past 10 years. Use case dictates hardware, not the reverse. With AI, we have an amazing use case today, but we also understand what smart glasses are. Smart glasses are eyewear. Smart eyewear.” That is, smart glasses are not a standalone consumer device like virtual reality headsets used for gaming.

Heilig’s Sensorama, an immersive artificial reality device. Photo credit: USC HMH Foundation Moving Image Archive

Meta’s Jason Hartlove says his company’s partnership with Ray-Ban has “shown us now what product-market fit looks like for a wearable compute device.” There’s no display in the devices currently marketed, however, they are AI integrated for tasks like real-time language translation. Their microphone arrays and high-fidelity audio output, he says, have “really created a new paradigm for wearable devices, especially eyewear.” Users can wear Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses to make calls, listen to music, and capture 12-megapixel ultrawide photos and videos that can be livestreamed on Facebook and Instagram. Users can also engage a digital assistant, Meta AI. The glasses come with a case that is also a charging device.

This year, Meta introduced its Orion model smart glasses, which have a more-than 70-degree-capable wide field of view, silicon carbide waveguides, an advanced micro-LED projector, embedded eye tracking, active dimming, and a variety of sensors and on-board cameras. “We have all the degrees of freedom tracked as you move your head around,” Hartlove says of Orion. “We know exactly where your eyes are going. We know exactly where the object should stay locked in the visual field, as well as the contextual AI”—all built into a glasses form factor weighing less than 90 grams, that is, glasses that can be worn all day.

Orion, Hartlove says, is Meta’s north star for what is possible with smart glasses technology. Plans are to market Orion smart glasses at a $700 to $1,200 price point, comparable to a personal computer. At SPIE AR|VR|MR in January, he showed a video clip of a customer using Orion to grocery shop. The glasses recognize objects on a shelf and can use AI to, for example, suggest possible recipes with the ingredients. The glasses add labels to the objects, and they stay fixed, which is important Hartlove says because it is true to human visual experience.

A key enabling technology of Orion is the use of silicon carbide. Hartlove says that with its refractive index of above 2.6, “we can really begin to create this kind of ultrawide field of view experience…. We view this as a critical enabling technology. We’re on a mission to help the industry move that forward.”

Other areas of smart glass/augmented reality development, Hartlove says, include a brighter light engine using micro-LEDs, and the challenge of integrating custom eyepieces for different styles, frame sizes, and prescriptions. He says that comfort and positive user experiences will remain paramount for avoiding negative perceptions of AR glasses.

Smart glasses will never have fully immersive displays—that would make them a different product entirely, Kress notes, and it would be hard to keep the weight down to something like an ideal 50 grams. But a little arrow “can actually change your life if that little arrow appears at the right moment and the right location.” It could also be a line of text, in the case of glasses that stream captions or subtitles, or it could be some kind of geo-location. “You’re walking down the street, you tell your glasses, ‘I’m hungry. Show me the closest pizza place.’ And there will be some kind of arrows or symbols displayed to guide you there.”

But smart glasses’ success in the consumer eyewear market also depends on maintaining a clear understanding of consumer motivations. “Why do people buy expensive eyewear?” Kress asks. “Because they want to look good!” Sixty percent of the population needs some level of vision correction, but why spend [up to] $500 on smart glasses when you could spend $10 at a drugstore?

Google Glass. Photo credits: Google Glass - Antonio Zugaldia

Because for many consumers fashion comes first, followed by prescription integration, and third, digital functionality, Kress answers. One hundred percent of the time, wearers will want to look good, and even if 90% of the time they might not use the digital functionality, “when you use it, it’s really handy.” Designers learned valuable lessons from the Google Glass market failure, and today’s smart glasses focus on attractive designs that users will want to wear.

The global sunglasses market was estimated at $23.52 billion in 2023 and is expected to reach $34.34 billion by 2030, marking it as a major industry according to Mordor Intelligence. Fashion is rated second among three factors driving industry growth. Mordor says sunglasses are increasingly viewed as essential fashion accessories. The other two industry drivers are increasing awareness of the need to protect eyes from UV exposure, and the demand for attractive, polarized sunglasses that offer superior glare reduction. Companies placing big bets on smart glasses are convinced that consumers will find the combination of fashion, AI assistance, and social-media compatibility irresistible. Google, however, is not developing hardware—i.e., smart glasses—anymore, Kress says; it is developing Android X, a smart glasses platform. The hardware will be developed by partners such as Samsung, XREAL, Sony, Lynx Mixed Reality, and others.

Kress recently was naturalized as a US citizen. He wore a pair of his smart glasses (he owns several brands) to the ceremony. “I actually shot the entire scene with my glasses—an American flag, the oath that I was reading. But nothing in my hands, no smart phone.” He says the glasses can pair with a smart phone via low-power Bluetooth technology to connect to the cloud.

With a multimodal AI assistant, Kress says, smart glasses are constantly interacting with the environment in tandem with the wearer. “For example, you’re walking around your house, you’re going to get the car, but you put the keys somewhere you don’t remember right now. The glasses followed you and they know exactly where you put your keys.”

“A camera that sees what you see, microphones that hear what you hear, and an AI agent walking alongside, knowing your history, knowing what you have done, knowing what you need to do,” he continues. “It’s just like your mom being behind you—without breathing down your neck!”

Probably most people wouldn’t want mom following them around. But smart glasses 2.0 have arrived at a time when influencers make big money off social media content creation, and nearly everyone else feels the need to document life events big and small on their favorite platform. The photo and video functions on Ray-Ban Meta and other smart glasses allow direct posting to social media from sunglasses on the wearer’s head. Built-in headphones allow the wearer to listen to music (no more digging around for earbuds in your backpack), and the AI assistant can help with a variety of tasks, like direction finding. They offer a compelling package of good looks and convenience. The smart glasses industry, just maybe, has met its moment.

William G. Schulz is Managing Editor of Photonics Focus.